When I lived in Canada for a while, I was always a little bemused by the Canadian approach to speed limits. The maximum allowed speed limit on the QEW and the 400-series roads around Toronto is 100km/h and yet if you actually do that speed you just about get run over. The locals routinely cruise the highways there at 120-130km/h and there’s no issue.

When I lived in Canada for a while, I was always a little bemused by the Canadian approach to speed limits. The maximum allowed speed limit on the QEW and the 400-series roads around Toronto is 100km/h and yet if you actually do that speed you just about get run over. The locals routinely cruise the highways there at 120-130km/h and there’s no issue.

I like to drive fast too, but it used to frustrate my sense of logic when I’d ask my Canadian friends why they didn’t observe the speed limit.

“Oh, it says 100,” they’d say, “but nobody actually drives at 100, we drive at 120.”

“Why don’t they just raise the speed limit to 120”, I’d ask.

“Because then people would just do 140” came the reply.

Apart from being a really strange view of human nature, I’d then ask, “Why don’t you just post the speed limit that you actually want people to observe and then enforce that, instead of having this vague gray area where people do what they aren’t supposed to do on the understanding that nobody really minds?”

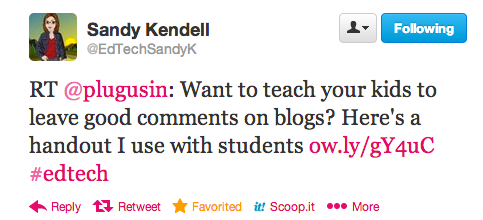

This same logic struck me today when I saw an RT from Sandy Kendell leading to a tweet from Bill Ferriter, an outstanding educator from North Carolina who shares and blogs a lot of his great work with the online community. It said…

I followed the link, and sure enough, it’s an outstanding resource rubric for helping students understand how to leave a good blog comment. I know that many teachers will find it a really valuable and useful resource.

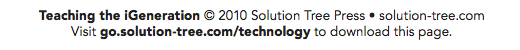

But then I noticed that there was a copyright notice at the bottom of every page that said…

The PDF resource seemed to be being given away freely on Twitter, but there was a fairly obvious Copyright notice at the bottom of every page. This struck me as odd, since Copyright essentially means that you cannot use a resource without prior permission from the author.

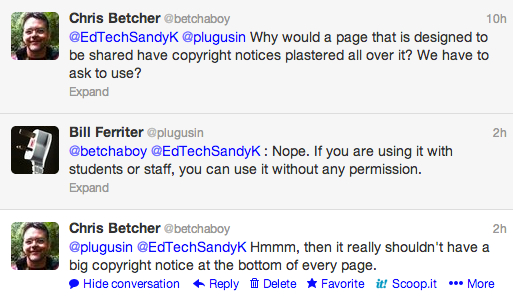

Following the link to “download this page” took me to the webpage where I could buy the book that this free resource came from. A little confused about how a copyrighted work was being given away so freely, I responded with a question on Twitter, phrased briefly to stick within the 140 character limit, which started a conversation with Bill…

To me, this is all just grey area. If there is an intent to share something that can be used without asking permission, then adding a Copyright notice to it really muddies that intent. The conversation bounced back and forward between Bill and I over Twitter, where I was making the point that, if it’s a free resource that is being given away, then perhaps a better way to do it would be to mark it with a Creative Commons license that clearly indicated up-front how users could make use of this PDF. Marking it with a CC BY-SA-NC, for example, would mean that it could be shared freely for non-commercial purposes, with attribution, and the permission to do so was being given in advance. This eliminates the requirement to contact the author to ask permission, since permission has been pre-given. That’s the whole point of Creative Commons.

By marking work with a Copyright notice it explicitly says that you cannot use this work without first asking permission. If people do actually follow the rules, that probably means Bill will be kept busy answering a whole lot of “Do you mind if I use your worksheet” emails.

In our twitter conversation Bill made the comment that it was his intention to make the worksheet freely available and that people were welcome to use it. The confusion arises because this same worksheet is very clearly marked with a Copyright notice. This is just like my Canadian friends who speed along the 100km/h QEW at 130km/h – the sign says one thing, but we do the other. In this case, we say that the resource is free to use, but we signpost it with a notice saying otherwise.

I’m not intending to single Bill out here… he does great stuff, is a prolific sharer online and I have great respect for him. The problem, as he pointed out to me, is that publishers still largely don’t “get” this stuff and they don’t know that alternatives to full copyright exist, or if they do they are too afraid to use them. As an author myself, it astounds me how out of touch most publishers are with the ideals of controlled sharing. There are tons of examples of “Don’t do what I say, do what I mean”. I just think it would be far better if we just said what we mean right from the start.

Bill was trying to defend the publishing industry, reminding me that they are just figuring this stuff out like the rest of us, but I think those of us who understand this stuff should make it our moral duty to educate those who don’t, and help them understand how some of the restrictions they instinctively use, like the indiscriminate stamping of Copyright symbols on everything they publish, work directly against our goals of sharing resources freely with colleagues.

As educators, many of us make things to share with our colleagues – videos, photographs, writing, music, etc. As creators and sharers of educational content, I think we have an obligation to make our sharing intentions crystal clear. If we intend to freely share our work, then we should clearly indicate that with the use of Creative Commons, Public Domain or some other open license that reflects our intent. If we want to protect our work and restrict access to it, then we should make use of Copyright. But I see a real problem when we confuse the message by not making that intent absolutely clear right from the start.

To paraphrase Dr Suess, you should always say what you mean, and mean what you say. Then there is no second guessing, no intuiting of intent, and everyone knows exactly where they stand.

![]() Rules are Rules. Sort of. by Chris Betcher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Rules are Rules. Sort of. by Chris Betcher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

I was bemused that in the USA, roadworks signs do not have lower speed limits, they ask drivers to slow down to the speed limit

As I mentioned in our Twitter conversation, the copyright notification that you reference here — and have embedded in this post — is referring to Teaching the iGeneration, the text that this handout is connected to. My publisher adds that statement primarily to point people who stumble upon the handout to the book that it came from.

The second line in your image — “Visit http://go.solution-tree.com/technology to download this page” — combined with the fact that the word “Reproducibles” leads off the collection of 70+ handouts that are available for download as editable PDF files on the book’s landing page is an indicator that the content can be widely used.

While I agree that the word “copyright” could just as easily be removed from the footer — and while I emailed that feedback to my publisher today — I’m thankful that the vast majority of readers aren’t confused by this.

Think about it this way: You’ve used my Tweets in your post without asking for permission in advance, right?

That is a violation of copyright too — which is immediately granted to the creators of written works in a “fixed and tangible medium” and automatically implied until intentionally waved.

Theoretically, then, you bore a responsibility to ask my permission to use that content in advance too, but you didn’t — and I’m not worried about it.

Why is that?

The answer is simple: The content is freely available — like the handouts from my book — in a forum designed for public sharing. That says to you as a consumer, “Go ahead. Use this even if you aren’t sure what my intentions are regarding my ownership of the content that you’ve found.”

And that says to me as a creator, “I’m posting this in a public forum designed for sharing and I have no protections on my stream of posts. There’s a real chance that my content will be freely shared and I have to be comfortable with that.”

The only difference in these two situations is that the word “copyright” doesn’t appear on my Twitterstream — but the absence of a copyright warning doesn’t matter. A creator owns copyright as soon as the content has been created in a fixed and tangible medium.

Regarding our “moral imperative” to educate and/or change the views of the publishing industry about Copyright versus Creative Commons, I think we will continue to see content creators — whoever (and however large) they happen to be — forced into a strange gray area for the immediate future simply because very few content consumers really know what Creative Commons is all about.

That leaves creators in the uncomfortable position of having to either use a license that no one understands and hope that users will respect the terms of that license or use a license that doesn’t fully express their views on how a piece of content can be used but that at least communicates a few basic messages — primarily, “you have to respect the ownership of this creative work.”

Neither solution is a good one.

Does any of this make sense?

Bill

HI Bill,

I take your point about the reuse of a Tweet, but there is enough of a debate about whether Tweets are in fact copyrightable that I remain unconvinced that they are.

Regardless, I think there’s still a big difference between putting a sub-140 character Tweet in a freely accessible public place designed to be shared like the Twitterstream, and placing a worksheet marked with a copyright notice in the footer of every pages on the same website as a book that sells commercially. Because these worksheets are made available on the very same webpage used to sell the book, the logical assumption of most people would be that these worksheets are included with the book (I’ve no idea whether they are or not) and are therefore subject to the same copyright restriction being applied to the book.

Quoting a Tweet, which is a generally accepted practice done by private individuals acting on their own behalf, is quite different to finding a worksheet online and making 150 copies to use with Year 10 on behalf a school. The liability implications of getting it wrong are quite different in each of these cases. While I understand the example you’re trying to provide between Tweets and your worksheets, I don’t think it stands as a good example of how copyright might apply.

There’s no guarantee that someone finding these worksheets does so by going to this website. They could be shared by a colleague, given as a printed copy or any other means… I would imagine that most people seeing a worksheet marked with a copyright notice and the name of a commercial publisher in the footer would just assume that the copyright limitations apply to the sheet itself.

Regardless of the content creators intent, there is so much room for misinterpretation unless these things are clearly stated. It sounds like you believe most people don’t understand Creative Commons and the various licence types, and maybe you’re right. But simply including the plain-language phrase “This worksheet is able to be used freely for educational purposes” in the footer would clearly articulate the intent of the author and resolve most of the confusion.

My point was not to argue about the value of the worksheets or your intent to give them away in whatever manner you choose. They’re great and I’m very glad you share them, so thanks.

My point was that when a content creator intends for their work to be used in particular ways, simply including a brief statement expressing that intent helps to remove much of this confusion.

At one point in our Twitter conversation Sandy made the comment “if the author of the document posts it for public consumption, that’s some implied permission right there.” Why should permission be “implied”, when with a just few well chosen words we can expressly state exactly what we mean and remove all doubt? I guess what I’m saying is that, in a school environment where the consequences of misinterpreting copyright and accidentally infringing the rules can lead to serious problems for both the teacher and the school, it’s worth making absolutely clear what the intent is so that we are not relying on people trying to figure out what the author was implying (or perhaps not implying)

And yes, I think as content creators, it’s up to us to educate the publishers that this is the new normal and it’s the way we want it to be, regardless of whether it fits in with their traditional view of copyright or not.

Hi Chris,

This is an excellent post and reminds me that I need to make the resources that I distribute on my blog very clearly marked with a CC licence.

Here is an example on a similar theme. I used to find that many teachers were using my class blog guidelines without any attribution or acknowledgement so I now write under the guidelines that teachers are welcome to use them and don’t need to ask permission but should attribute the source. The funny thing is I still get SO many people asking for permission via the blog or email. It gets annoying! Is there a solution to that?

The whole Creative Commons/copyright issue seems to be the source of a lot of confusion for teachers. In fact, many teachers don’t seem to know anything at all about Creative Commons/copyright which is quite alarming.

Cheers,

Kath

Hi all,

What an intriguing blog post, it certainly captured my attention. Confession time, I only stumbled upon your blog from your twitter account recently however it is now in my feed to read :).

I would like to tackle this from a slightly different angle. That is the side of copyrights “fair dealing” exception which is pointed out here Smartcopying. To summarise as long as taking a reasonable portion of the book, it is permissible for students/teachers to use as a reference though they are not able to make many copies of the paper. However under the Education licence B it is permissible.

For me the reason of marking copyright on a sheet is pretty simple, it would be for other authors and text book companies can just take and re-use this sheet in their own books.

p.s. hope these links work.

Hi Justin,

Thanks for the thoughts and the links. Fair Use or Fair dealing, depending on what country you’re in, certainly gives educators a lot more freedom to use copyrighted material than we often realise. I know that many school systems pay quite hefty royalty fees in advance to be able to make use of such resources.

The problem is compounded by the fact that so much of what we get our kids to do these days can end up back in the public sphere. When a student or teacher uses found resources to produces a piece of work for whom the audience is only the class and the display of that work extends no further than the pinboard at the back of the classroom, then you can get away with basically using anything and claim it’s a case of fair dealing.

However, if you start to take material off the internet, and use it, copy it, remix it, etc, and then allow your derivative work to find its way back out onto the internet, that’s a whole different story. And it’s increasingly the case with the types of things we do in schools these days.

There are some instances where it’s very clear that a copyright has been infringed (if you buy a DVD and make copies to give all your friends, for example) but in the education field there tends to be many more uses that fall into the grey area of uncertainty.

The interesting thing about a copyright violation (as I understand it) is that it’s not a violation until it’s proved to be a violation, and the decision about whether it is or isn’t a violation is often made after the fact. In other words, if I make something and you reuse it, and I feel you’ve infringed on my copyrights and you feel you haven’t, then we are at an impasse. We are in that grey area where each of us is in disagreement about whether the material has, or hasn’t, been used in an inappropriate way. The resolution of that disagreement is ultimately made in court, where we each explain to the judge why we believe the use of the material either is, or isn’t, in violation of copyright law. The judge then looks at the way the law applies, takes into account the extent (if any) of damages and lost revenue, harm to reputation, etc, and makes a ruling. But really, up until the point of that ruling, there is often no clear answer about whether a particular use case in in violation of copyright or not. (Obviously, I’m only referring here to uses that sit in that “grey area”)

A lot of this can be avoided if owners of intellectual property made a greater effort to be clearer about how they are prepared to let people use their work. This is why Creative Commons is such a brilliant idea… it provides six different licence types that range from ALMOST completely free and open (CC BY) through to ALMOST full copyright (CC BY-ND-NC), with varying levels of “free-ness” in between.

In your example of adding a copyright notice to a resource you make, so that people can’t just rip off your resource to include it elsewhere or publish it in a book, you could get the same level of protection if you used a Creative Commons licence, but it would also allows other to use that resource as long as they stay within the guidelines of the CC licence. By adding the NC (Non Commercial) option you would prevent textbook companies and anyone else trying to commercialise your work from using it without your permission. Including the ND option (No Derivative works) you would prevent others from changing or modifying your original resource), or by including the SA (Share Alike) option, you would prevent anyone from taking your work without also requiring them to allow others to take the work from them. And of course, all CC licence require attribution (BY), so your name as the author should always accompany any use of the work.

Using a CC BY-ND-NC licence on your work essentially says “You can use this work without asking for permission, as long as you include a citation to me as the author, you don’t change it from its original form, and you don’t use it for commercial purposes. If you want to change it, or want to use it commercially, then you need to contact me and ask and I will decide if I will allow it.”

And really, isn’t that the best of all possible worlds?