The school at which I teach, PLC Sydney, was in the news this morning regarding a recent assessment task conducted by one of our Year 9 English classes. The article from the Sydney Morning Herald talks about how this class is pushing the “open book exam” concept into allowing students to use resources that take them beyond the boundaries of the classroom and enable them to draw on outside sources – the web, other books, their own personal networks – using whatever tools they choose – mobile phones, computers, iPods, PDAs, etc – in order to be assessed on their learning.

The school at which I teach, PLC Sydney, was in the news this morning regarding a recent assessment task conducted by one of our Year 9 English classes. The article from the Sydney Morning Herald talks about how this class is pushing the “open book exam” concept into allowing students to use resources that take them beyond the boundaries of the classroom and enable them to draw on outside sources – the web, other books, their own personal networks – using whatever tools they choose – mobile phones, computers, iPods, PDAs, etc – in order to be assessed on their learning.

I actually had a meeting with their teacher, Deirdre Coleman, about this idea the other day and we discussed at length some of the pros and cons, what sort of tasks were best suited to this approach, where the boundaries lay between cheating and resourcefulness and so on. While the SMH article is mostly accurate in its reporting, some of the value judgments that appear from reading between the lines are a little off-target, as are many of the comments from readers that have flowed on as a result of the article. Unfortunately, the article almost suggests that at PLC we are not actually teaching these students but rather just setting them loose with a cellphone and a phone-a-friend and seeing what happens. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Whether you think that allowing students to use tools like computers and mobile phones during an exam is a good idea or a bad idea is somewhat dependent on what you see the purpose of school to be. It also depends on your world view and whether you see information as scarce or abundant.

It ought to be obvious to anyone with a modicum of common sense that the model of school we all know so well – the model in which students come to school as essentially empty vessels waiting to be filled by the teacher – is hopelessly flawed and outdated in this day and age. Sure, there was a time many years ago when most students did not have access to large quantities of information. When I was a kid, the sign that your parents were really interested in giving you the very best educational opportunity was that they bought an encyclopedia for the home. In our house we got the World Book. It still sits on the bookshelf at my mother’s house, outdated and gathering dust, far too expensive to be thrown away despite its expired use-by date.

The idea of buying your kid an expensive encyclopedia was based on the notion that information was scarce… if you didn’t have an encyclopedia then where on earth would you get information from? Those students who did not have an encyclopedia at home were limited to going to the local library. Of course, the other major source of knowledge was the teacher at school, who could teach you all about the things that the curriculum deemed as important. Wonderful things like Euclidian Geometry. Quadratic Equations. Shakespearean Sonnets. The Periodic Table.

The thing is, at 45 years old, I cannot remember the last time I needed to use the Quadratic Equation. Or recite a Shakespearean sonnet. And although I did recently get asked a question about an element on the Periodic Table, I still had to look up the answer anyway.

For the record, I was actually a pretty good student in school. I was mostly bored by school, but I did do ok at it thanks to the fact that I’m relatively smart and was good at remembering stuff in order to pass tests. There was a time when I really did understand and could apply the Quadratic Equation, I knew how a sonnet was structured and I could rattle off at least the first 25 or so elements of the Periodic Table. It’s not like I never learned this stuff… I did actually learn it and passed tests on it with good results.

But so what?

These days, if you ask me to tell you what a sonnet is, I would still need to look it up. I would no longer be able to describe the Quadratic Equation to you with any certainty, and as I mentioned, I’d probably want to double check the Periodic Table before I relied on my own recollections about it. The fact that I did actually once learn this stuff now has little to do with it. The real skill now is not whether I can remember it exactly, but rather, do I have the ability to find, process, use and apply the relevant information in order to solve a problem at hand.

Which brings us to the idea of information abundance. We have to get past the idea that learning is about clinging to the handful of facts and ideas that fill our curriculum. For every concept and idea deemed worthy of inclusion in our curriculum, there are hundreds of others that don’t get included. Why do we learn about the language used by Shakespeare in his sonnets, but not how to write a good press release? Why do we have students who can complete a quadratic equation, but haven’t the faintest idea about how to get a good deal on their first car loan? Why do we learn about volcanos in Science, but not hydrodynamics? Why do we focus on the history of WW2, but not the history of the Central American drug wars? It’s not that any of these things are more virtuous or more important than the other, it’s just that we have only so much time in the school day, and we can’t fit everything in so we choose a more-or-less random selection of ideas and concepts and call that our curriculum. Everything else, regardless of whether students might find it interesting or not, does not make the cut and is therefore deemed as unimportant for learning.

Meanwhile, new knowledge grows at an unprecedented pace. The human race discovers new things almost daily. Thousands of new ideas are patented every year. Billions of webpages hold information and opinions on every conceivable topic you could imagine. Huge networks of people constantly build knowledge and understanding about our world. Information is no longer scarce. We are swimming in it, sometimes even drowning in it.

The real skill, to again quote Seymour Papert, is not that our students should be able to respond correctly to the things they were specifically taught in school. The real skill is that they should be able to respond appropriately to things that they were NOT specifically taught at school. We need to prepare them not to know answers, but to solve problems. And in a world where many of the problems to be solved have not yet even been identified as problems, how do we prepare children for this future that does not yet exist?

I’d suggest that we DON’T do it by presenting them with a narrow body of information dictated by some arbitrary curriculum, and then “test” them on their understanding of it by isolating them and asking hypothetical questions aimed at seeing how much they can remember about it. I’d challenge you to provide a single example, outside of schools and universities, where this type of method is used to determine a person’s real understanding or knowledge.

In any other profession, the idea that you are limited only to what someone has already taught you is absurd. The thought of a doctor only operating within the bounds of her own memory and being forbidden from “looking things up” is ridiculous. I don’t want to go to a doctor who cannot find the information I need when I need it. I don’t want to go to a doctor that is unable to extend their thinking beyond what they were taught in medical school. I need a doctor who can think holistically, use intuition effectively, connect seemingly unrelated ideas, find current research and communicate with other expert practitioners to get the answers I need.

It doesn’t matter what field of endeavour you think about, from archeologists to zoologists the real measure is not how many marks they got in a test of rote memory, but in how well they are able to use the resources at their disposal to solve the problems in front of them. If that means they need to Google for an answer, call someone for a second opinion, or grab the manual to look something up, then that ought to be ok. It’s about getting the problem solved and if they need to use their resourcefulness or contacts or tools to solve the problem then so be it.

The class at PLC is trying to offer students the opportunity to do the same kind of thing. We want our students to think. We’d like them to be creative and resourceful, using the tools at their disposal to find effective answers to the problems they are being asked to solve.

The people in the SMH comments feed who keep referring to this as cheating don’t really get it. Of course, everyone is an expert when it comes to school – after all, we all went to one at some point, so of course we understand how they work. I keep reading comments in the feed that talk about how it was not like this when they were a kid, about how the system of rote learning worked for them (as though the world is still the same), about how we need to teach kids to pass exams because that what universities expect (and the rest of the world?)

Even if I didn’t actually work at PLC, I’d still applaud them for taking these small steps towards something that ought to be so plainly obvious to everyone involved in education… that we need to recognise our students as real learners, doing real tasks in the real world using real tools. We need to stop thinking about how school always was in the past and start getting our students to think about how they should operate in a world that rewards results.

Good on you PLC!

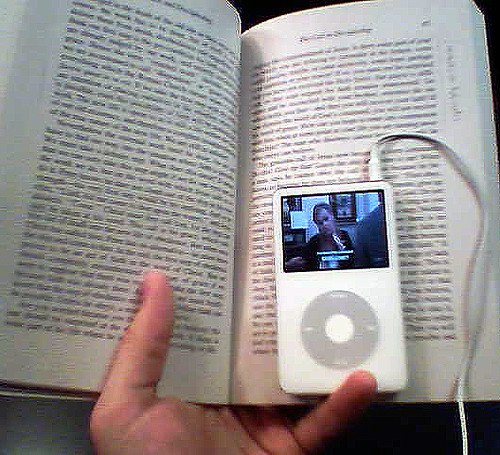

Image: ‘“Studying for class”‘

www.flickr.com/photos/30885355@N00/109039319

Tags: smh, plcsydney, plc, mobilelearning

One of the real joys of my current job is that I get to work with our younger students in the primary school. Having only ever taught high school, the chance to work with the R-6 kids is just so refreshing. They are so enthusiastic, so keen and so refreshingly honest. I’ve had a great time this term working with all the Junior School kids, but in particular I enjoyed working with Year 3 on some digital storytelling projects, where I suggested to the Year 3 teachers that they try

One of the real joys of my current job is that I get to work with our younger students in the primary school. Having only ever taught high school, the chance to work with the R-6 kids is just so refreshing. They are so enthusiastic, so keen and so refreshingly honest. I’ve had a great time this term working with all the Junior School kids, but in particular I enjoyed working with Year 3 on some digital storytelling projects, where I suggested to the Year 3 teachers that they try