In 1963, when I was born…

In 1963, when I was born…

Television was delivered over the airwaves. In black and white. We had four channels to choose from and we had to get out of our seat to change them. And we hardly ever heard a swear word.

Radio was only available using an AM signal. In mono. If you didn’t like the song that was on, you could switch to the other station. If you wanted to listen to music on the go, you had a small transistor radio with a tinny speaker or a single earpiece. And if you wanted to hear “your show”, you had to listen while it was being broadcast.

Newspapers were printed on paper and printed every 24 hours. The time between a story happening and us finding out about it was often several days. Which stories made it into the newspaper was decided by an editor somewhere. The text on the page was made by rolling ink across the tops of slugs of lead in shape of letters, assembled to make sentences, and then pressing those inked letters against paper. The paper was then folded, cut, bundled onto trucks and delivered to your local newsagent where you had to go to buy it.

Photography required the use of film, a long strip of plastic covered in a silver emulsion. You could take either 12, 24 or 36 photos at a time. Once you’d taken all the photos that would fit on the roll (and only then), you had to send them away to be developed. This usually took about 2 weeks.

Moviemaking also required film. It was a continuous strip of 8mm wide plastic and required a dark room and a projector to view it. Each reel went for 3 minutes. They were expensive to process, and hardly anyone ever bothered to edit them. Having sound was an expensive luxury.

Music was stored on round black disks called records, which had long spiral grooves etched into them that mirrored the soundwaves that described the music. It was, quite literally, an analog of the waveform. Later, you could get audio cassettes that could hold either 60 or 90 minutes of music. You had to flip them over halfway through, usually in the middle of a song. Solving technical problems with cassettes required the use of a pencil. The audio quality, in hindsight, was awful.

Telephone calls were made from home, sitting next to the phone. If it was a long distance call you had to think in three minute blocks of time. You only called long distance on special occasions like Christmas or birthdays, and you had an egg timer sitting next to the phone. Telephones were made for making telephone calls. That’s all.

Telephone calls were made from home, sitting next to the phone. If it was a long distance call you had to think in three minute blocks of time. You only called long distance on special occasions like Christmas or birthdays, and you had an egg timer sitting next to the phone. Telephones were made for making telephone calls. That’s all.

It’s now 2013.

In those 50 years that have passed, most people would agree that some of these things have undergone a few changes, and those changes have occurred mostly because they went digital.

Television went digital. It is now far more likely to be delivered over a cable In full high definition colour and 3D, with 5.1 surround sound. If you don’t like what’s on, you can choose from hundreds of other channels. If you want to watch something else entirely, you can stream on demand via YouTube or some other web-based video service. Oh, and there probably will be swearing. Lots of swearing.

Radio went digital. You now have dozens and dozens of high quality FM transmissions to choose from. You can take your listening mobile in your car, or go portable on your MP3 player or phone. You can timeshift your listening by storing your favourite radio shows as podcasts and listen whenever it’s convenient. Or listen to stuff that you find interesting that would never make it on the radio. All for free.

News went digital. Multiple streams of news, based on your interests, can be delivered to you almost as it happens. You can choose your sources; global, local, hyperlocal. You can contribute to the stream if you choose. You can comment, argue, debate. You can participate. Twitter redefines what we mean by news, and can help start revolutions in the process. We can find out about anything, anytime, anywhere. For free.

Photography went digital. You can now take as many photos as you want, in massively high resolution. You can see them immediately after you take them. You don’t have to wait. You can enhance them, fix them, or delete them if you don’t want to keep them. You can share them instantly with anyone, anywhere in the world. Immediately. For free.

Moviemaking went digital. You can now shoot movies in ultra high definition. With sound. You can view them immediately, edit them in ways that only professional studios could once do, share them easily with your family and friends. You can send them to any device you like, to watch right away. For free.

Music went digital. The processes for creating, storing, distributing and sharing music are dramatically different. Using services like iTunes, Pandora or Spotify, you can listen to any music you like, whenever you like, however you like, on whatever device you like. It’s delivered in high quality stereo. It’s editable and remixable. You can swap and share music with others, anywhere in the world. For free.

Communication went digital. Telephones have morphed into mobile “devices” that can be carried anywhere, making you contactable wherever you are. Voice signals now travel the world over thin glass threads at the speed of light. VOIP software like Skype or Google Voice let you talk to anyone, anywhere, for as long as you like, with multiple people. With video too if you want it. For free.

And the best part of all? Because all of these things share the same digital heritage of zeros and ones, they can be easily mixed and mashed, and can live on the same clever device, bringing us true digital convergence.

So think about it. Think about just how much the rules have changed. In a mere 50 years – barely a blink really – we have gone from a world where things that were hard to do have become easy, things that were time consuming to do have become instant, things that offered few options now come with seemingly unlimited choice, things that were expensive have become virtually free, things that were once scarce are now abundant.

Think about what that does to the world. What happens to economics when scarcity swaps places with abundance and expensive things become free? What happens to the human experience when time-consuming things become instant and difficult things become easy? What happens to society when things that once required special training and special equipment are now within the reach of anyone who wants to do them?

In less than 50 years we have essentially shifted from an analog world to a digital world. The implications of that change have affected virtually every field you can think of. It’s difficult to imagine how an industry like banking or travel could possibly have ever functioned without the use of digital information and communication technologies. Like it or not, this digital genie is never going back into the bottle.

So, what are your survival strategies for a digital world?

What sorts of things do you do to feel at ease in a digital world?

What are the essential skills, mindsets and attitudes that one needs for a digital world?

What moral and ethical stances make sense in a digital world?

How do you become a productive, responsible citizen in a digital world?

How do you stay safe in a digital world?

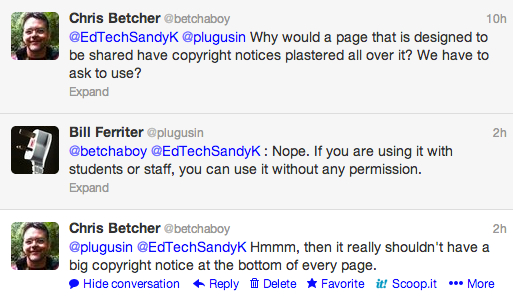

How do you decide what is public and what is private in a digital world?

How much do you share in a digital world?

What defines appropriate in a digital world?

These are the sorts of questions we should be asking ourselves as we aim to be productive members of a society gone digital. Ironically, while some of these things require a serious rethink, many of the answers may simply be an evolution of those that applied in the analog world. The question is, which ones?

And once you figure it out, how do you help children figure it out? Because for them, this is the only world they’ve even known.

In 1963, when I was born…

In 1963, when I was born… Telephone calls were made from home, sitting next to the phone. If it was a long distance call you had to think in three minute blocks of time. You only called long distance on special occasions like Christmas or birthdays, and you had an egg timer sitting next to the phone. Telephones were made for making telephone calls. That’s all.

Telephone calls were made from home, sitting next to the phone. If it was a long distance call you had to think in three minute blocks of time. You only called long distance on special occasions like Christmas or birthdays, and you had an egg timer sitting next to the phone. Telephones were made for making telephone calls. That’s all.