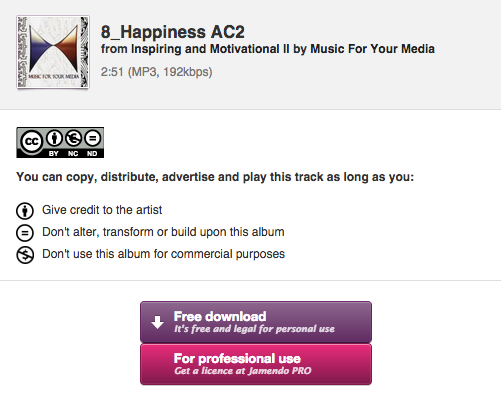

A few weeks ago Linda and I got home from a short holiday in Bali. We had a great time, and managed to collect a few snippets of video along the way using a GoPro camera. A few days after I got home I managed to stitch a few clips together into a little video summary of the holiday using my own footage and some Creative Commons music that I sourced from Jamendo, one of of my favourite sources for CC-licensed music. I used a happy little track called “8_Happiness AC2” by an artist called “Music for your Media“. The track was licensed under a CC BY-ND-NC licence – meaning that if I attribute the artist (I did), don’t modify the music (I didn’t), and not make money from its use (I’m not), I was welcome to use it. That’s the nice thing about Creative Commons licensing; the terms and conditions of use are clear, explicit and fairly unambiguous.

Or so I thought.

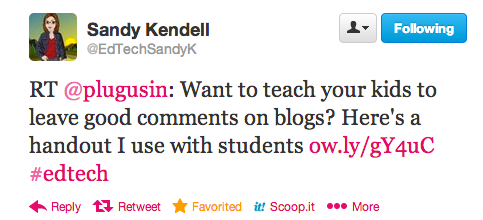

After I edited the video – all 2 minutes and 52 seconds of it – it was published to YouTube. The next day I received a notification from YouTube saying that the sound track used on the video was a copyright violation, and that it contained “Disputed Third Party Matched Content”. In other words, someone was claiming that I’d used the music without the correct permissions from the copyright owner.

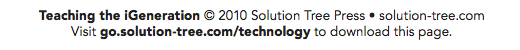

I don’t believe that it is “Disputed third party matched content”. I sourced the music track as a Creative Commons media asset, which was clearly indicated in the download link on the Jamendo site, as shown here…

“Free and legal for personal use” seems pretty unambiguous to me.

The Jamendo website also has a nice simple explanation of Creative Commons files on its FAQ page…

“Jamendo can be free and legal thanks to Creative Commons licenses. They grant the right to download and share music for free and legally. Artists choose to use these licenses, and to use Jamendo as a means to share and promote their music.”

“Creative Commons are licenses that enable musicians to give away their music for free while protecting their rights. They are easy to use and compatible with internet standards, and allow rights holders to authorize (or not) certain uses of their music, such as commercial uses and derived works.”

There was a link in my YouTube Video Manager dashboard to dispute the claim, so of course I disputed it. I provided the links to the site that I got the file from, pointed out it was a CC track, and assumed that would be the end of it.

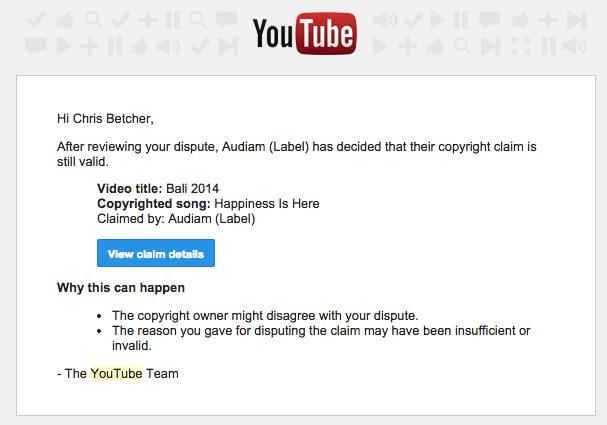

Then today I got another notification from YouTube that my dispute had been rejected and that the original claim of using Disputed third party matched content would be upheld.

As a longstanding supporter of Creative Commons, I was pretty pissed off that the “copyright holder”, a label called Audiam, was jerking me around like this. The track I used was clearly a Creative Commons track and my use of it was clearly within the requirements of the BY-NC-ND license. I have my own suspicions about why they are making this claim, but I’ll save the theories for now. I don’t know what deal Music for your Media may have done with Audiam, but I do know that the file I sourced was issued under a clearly defined, non-revocable CC license.

Feeling very annoyed, I decided to appeal the ruling because in this instance I’m convinced I am right. Although it would be trivially simple to just substitute another piece of copyright free music from the YouTube media library and be done with it, it’s the principle that matters here.

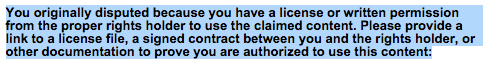

So I clicked the link to appeal the dispute and provided the following information to YouTube…

Thanks for looking into this alleged infringement and making a ruling but NO, I cannot agree with this ruling. I know it would be far simpler to just remove the video from YouTube or to replace the soundtrack with a different piece of music, but there is a principle at stake here. I believe that your ruling is incorrect and I’d like to dispute it further. Despite the risk I take in having you find against my use of the music again, I know that I am in the right and I want to defend my use of Creative Commons licensed material.

The piece of music in question, “Music for your Media – Happiness is Here” was sourced under a Creative Commons license from Jamendo, one of the Internet’s major sources of Creative Commons music.

The link at which I retrieved the MP3 file was this page… https://www.jamendo.com/en/track/1147331/8-happiness-ac2

When clicking the Download button on that page the license terms of the music are displayed as Creative Commons BY-NC-ND

Use of the track is clearly summarised on the download dialog as follows…

Some Rights Reserved – Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs CC BY-NC-ND

You can copy, distribute, advertise and play this track as long as you:

Give credit to the artist

Don’t alter, transform or build upon this album

Don’t use this album for commercial purposes

I have not violated any of those terms. The music is credited in the closing credits of the video, I have not altered or remixed the track. I have not used it for commercial purposes, it’s simply a personal video about a holiday I took in Bali. (non commercial even includes the fact that YouTube ads are turned off for this video)

I am a longtime user and contributor of Creative Commons material. I am well aware of how CC licensing works and it seems very clear to me that this work was released under a Creative Commons license, and that my use of it was well within the requirements of that license.

I should also point out that CC licenses are not revocable. As stated on the Creative Commons wiki FAQ, “CC licenses are not revocable. Once something has been published under a CC license, licensees may continue using it according to the license terms for the duration of applicable copyright and similar rights. As a licensor, you may stop distributing under the CC license at any time, but anyone who has access to a copy of the material may continue to redistribute it under the CC license terms.”

So even if Audiam, the label claiming ownership of the music, has changed their mind about the licensing of this track, this does not affect my use of it.

To sum up, I have sourced this track legally and through legitimate means. I have completely complied with the terms of this non-revocable CC license. A CC licence is a pre-granting of permission to use a media asset. I do not need to contact the copyright owner to seek permission because that permission has already been granted.

I fail to see how this could possibly be seen as a copyright infringement, and I hope that common sense and a more complete application of the principles of Creative Commons prevails.

I await your response.

Let’s see what happens. I’ve heard of people making these spurious copyright claims before but this is the first time it’s happened to me. The reason is generally that if they win they get the right to place their ads on my video and earn money from them. Most people don’t bother fighting it because it’s simply too much work to appeal, it runs the risk of getting a copyright strike against your YouTube account if you lose, and it’s just far easier to roll over and give in.

Not me, not this time. There is an important principle of freedom at stake here and that’s worth fighting for. I’ll let you know what happens.

Featured CC Image by Kev-shine on Flickr