Imagine this scenario… you are suddenly diagnosed with a life threatening disease, something very dangerous but quite curable if you have the right information about how to do so. Your doctor knows that there is an answer to your serious problem, but cannot recall what drug is required to treat it. He remembers reading something about it a long time ago, but can no longer recall the exact name of the drug.

Imagine this scenario… you are suddenly diagnosed with a life threatening disease, something very dangerous but quite curable if you have the right information about how to do so. Your doctor knows that there is an answer to your serious problem, but cannot recall what drug is required to treat it. He remembers reading something about it a long time ago, but can no longer recall the exact name of the drug.

He reaches towards the mouse on his computer, and begins to click a link that will take him to the online medical directory where he will find the answer he needs to cure your condition.

“Stop!”, you declare. “That’s cheating! If you can’t remember the name of that drug without looking it up, then what sort of doctor are you? I want you to just remember it without looking it up.”

Of course, I imagine that if this situation were real you would be only too happy for the doctor to do whatever was required to find the cure for your disease. You wouldn’t think twice about whether it might be considered “cheating” to look up the information needed to save your life… in fact you’d better hope that you have a doctor who a) knows there is an answer out there somewhere, and b) knows how to find it quickly.

I pondered this scenario today because I went to a dinner party with about 40 other people and we were presented with a trivia quiz on the table, something to keep us busy and entertained between food courses. Being a celebration of Canadian Thanksgiving, the questions were all about Canada. Now, I actually know quite a bit about Canada… I lived there for a year, travelled quite extensively through the historic eastern provinces, read a few books about Canadian history, and I have a Canadian girlfriend. So I did know the answer to quite a few of the questions.

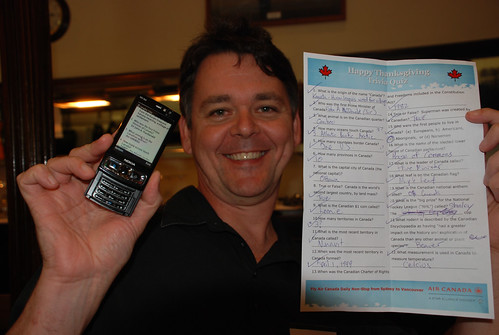

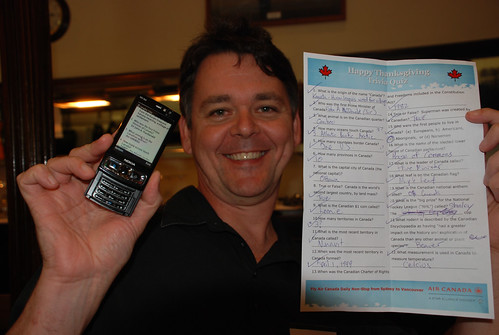

Of course, there were also questions I didn’t know the answer to. And being the curious type who likes a challenge and to always learn more, I reached for my Nokia N95, pointed it to Google, and started looking for the answers to the questions I didn’t know. If you have reasonable information literacy skills and can come up with good search keywords, finding answers to simple recall-style questions with Google is pretty easy. In fact, you can usually find the answers just from the Google search results page without even going to the websites they link to. It was not long before I had the elusive answers… in fact, I actually stumbled across the exact quiz that the questions were lifted from. Whoever put the quiz together had not changed anything, just used it directly from this website. I casually copied down all the unknown answers onto the sheet and waited until it needed to be submitted.

Of course, when the sheets were finally collected and tallied, there was general astonishment that someone could have actually gotten all the questions 100% correct! A few people who knew what I’d done bandied about words like “cheating” and “unfair”.

For the record, I did not accept the prize – a lovely bottle of red wine – because I willingly admitted I had some help from my friends Mr Google and Mr Wikipedia, and I figured it would not have been fair to accept the prize. I guess I just like to be a bit of a stirrer sometimes in order to make a point, even if only to myself.

But seriously, why do we build entire education systems based on rewarding people who can respond with the correct answers to questions, but then assume that any use of a tool to help them do this is cheating? Why would a doctor in the scenario above get applauded for doing whatever was necessary to find an answer to the problem, but a student who does the same thing is considered a cheat.

If basic recall of facts is all that matters, a tool like Google can make you the smartest person in the room. Today’s trivia quiz proved that. If finding answers anywhere at anytime is a valuable thing to be able to do, then a mobile phone should be a standard tool you carry everywhere.

What I think people were really saying was that, if I was allowed to use my phone to find answers and everyone else wasn’t, then that would give me an unfair advantage. And that may be true if I was the only person with access to Google, but the fact is that I didn’t do anything that every other person in that room could have done if they’d have chosen to. The fact is, I was the only one in the room who used a tool that we all potentially had access to, but because I used that tool it made me a “cheat”.

And here’s the real point… mostly we ban these tools in our classrooms. And we generally consider any student that uses such tools to find answers to our narrow questions to be a cheat. And we drill into kids that when we ask them questions, when we set up those “exam conditions”, they better not even think about being “enterprising” or “creative” or “problem solvers”… Just know the answers to the questions, and show all your working too, dammit.

And you’d better hope that if one of those students ever grows up to be your doctor, the rigid thinking we may have instilled in them about “knowing the answers” has been replaced with a far more flexible skill for “finding the answers”. Let’s hope that our kids don’t have too much trouble unlearning all the bizarre thinking that schools spend so much time drilling into them.

What do you think? At what point does the ability to find answers cross the line and become cheating?