I think I can safely say I’ve just been to one of the best conferences I’ve ever attended. It was well run, well organised and I believe provided content that was highly relevant to all the participants. The irony is that the day before it all started, it was completely unorganised and had virtually no content planned at all. I’m talking about the Learning 2.010 Conference held last week at Concordia International School in Shanghai, China.

I think I can safely say I’ve just been to one of the best conferences I’ve ever attended. It was well run, well organised and I believe provided content that was highly relevant to all the participants. The irony is that the day before it all started, it was completely unorganised and had virtually no content planned at all. I’m talking about the Learning 2.010 Conference held last week at Concordia International School in Shanghai, China.

I think it’s really important to draw a clear distinction between being unorganised and being disorganised. Disorganised is when things are a complete mess, no one has any idea of what’s happening, people are not getting their needs met and it leads to frustration for everyone involved. This conference was definitely not disorganised.

Unorganised, on the other hand, implies a understanding that learning is messy and that when we need to learn something we learn it best if we can learn it just-in-time, not just-in-case. When you put together a conference about learning, being unorganised means recognising that you can’t meet someones needs until you know what those needs are. Being unorganised means that you don’t assume that you know what’s best for people, but rather, you ask them what they need. Being unorganised implies flexibility, adaptability, and a willingness to listen to what people really want, at the point when they want it.

It also implies a huge risk, since you are inviting people to attend (and prepay for) an event that essentially does not yet exist. It would be far easier, far safer, far less risky, to run a conference the way they are traditionally organised… Bring in some smart people to speak, get them to stand on the stage and impart their wisdom to the assembled masses, and perhaps preplan some added workshops on what you think people need. That’s the accepted way to run a conference, the safe way, the “normal” way, the organised way… doing it any other way is a risk and a challenge to the status quo, and potentially a threat to people’s expectations.

However, those with the goal of shifting and reshaping education know inherently that this traditional model of conference planning flies in the face of what we proclaim learning is truly about. It’s ironic (and hypocritical) that conferences about contemporary learning should remain modeled on a structure that so blatantly contradicts the way we keep saying that learning should work in the 21st century.

The organisers of Learning 2.010 accepted this risk and, from what I could see, it paid off handsomely. The event was run on the basis of having two quite different component parts… the first was based on a cohort (team) of learners that gathered around a key idea and worked together to explore that idea in depth over the two days, and the second component was an unconference that ran 90 minute workshops in whatever content emerged from the participants.

The cohorts were led by a team of international educators who were hand picked by the Learning 2.010 organisers (or should that be unorganisers?) and I felt extremely honoured to have been included in this group. These are some of the smartest, most forward thinking, contemporary educators I’ve ever had the pleasure to work with, many of whom I already felt I knew well from their blogs and online presence. There were many that I’ve wanted to meet in person for a very long time and others I hadn’t previously known of, but it quickly became pretty clear that this was an extraordinary group of talented educators.

As one of the invited cohort facilitators, I arrived into Shanghai the day before the conference started so I could be part of a brainstorming and planning session with the other facilitators about what and how we might make the cohort component of the conference best happen. Although we did have general themes to guide us, the exact structure of how we’d run the sessions, what resources we’d include, how we’d manage our cohort groups, etc, was all fluid… essentially, we had four 90 minute sessions over the 2 days and we could do whatever we wanted in them. Most themes had two cohorts, each with its own facilitator, that could be run independently from each other, or could be combined together, or some combination of these.

I was lucky enough to be teamed up with Melinda Alford, a teacher at Concordia (the host school) on the topic of Creating a Culture of Learning and Creativity. Originally from Atlanta, Georgia, but having now worked in Shanghai for the past six years, I’d not met Melinda before… in fact she was one of those teachers that wasn’t even on my PLN radar. But after working with her for a few days I have to say she is one of the most talented natural teachers I’ve ever met and it was a real joy to be able to work with her. It’s so nice when you get to work with someone who is really on the same wavelength. who shares so many of the same ideals about learning and education and is so easy to work with.

I was lucky enough to be teamed up with Melinda Alford, a teacher at Concordia (the host school) on the topic of Creating a Culture of Learning and Creativity. Originally from Atlanta, Georgia, but having now worked in Shanghai for the past six years, I’d not met Melinda before… in fact she was one of those teachers that wasn’t even on my PLN radar. But after working with her for a few days I have to say she is one of the most talented natural teachers I’ve ever met and it was a real joy to be able to work with her. It’s so nice when you get to work with someone who is really on the same wavelength. who shares so many of the same ideals about learning and education and is so easy to work with.

As we started to plan how our cohorts would operate, we decided not to run in two groups, but rather to combine them into one. Our general plan was to facilitate a guided conversation about the ideas of creativity and curiosity in learning, follow it up with some ideas and examples and strategies for developing creative opportunities for students, and then allow our group to organically break up into small teams based on interest and need, and produce something to share with the whole group in the final session. The “something” was open-ended, but was basically a resource, an activity, a plan, something, that could be put to use the next week in their classroom. We wanted to challenge the thinking of our cohort, but be practical and get them to actually create something they could use. We were also very focused on the idea of creating a learning environment for our cohort participants that modeled the type of learning that we were expecting them to create for their students… open ended, flexible, learned centered, challenging, hard fun. Our plan was to facilitate, not lecture. Share, not teach. Encourage, not demand.

We spent part of that first planning day tossing ideas around and creating some visual prompts. One of my big beliefs about the notion of creativity is that it should come from both sides of your brain. We were both very keen to encourage the idea that creativity is not something that just applies to “the arts”, not something that you only find in strange “arty” types who dress in strange clothes, not something that is applied to problems occasionally in a superficial way… we wanted to get the idea across that creativity is a critical thinking skill that applies to all disciplines, in all sorts of ways, all of the time. Melinda and I both had backgrounds in the creative arts as well as science and engineering, so we found it easy to weave this into our planning. To make the point, at the social event held the evening before the conference officially started, we got up on stage to promote our cohort sessions, me dressed in Elmo pyjama pants and a set of large donkey ears, and Melinda in a giant chicken outfit. At least we got noticed!

We spent part of that first planning day tossing ideas around and creating some visual prompts. One of my big beliefs about the notion of creativity is that it should come from both sides of your brain. We were both very keen to encourage the idea that creativity is not something that just applies to “the arts”, not something that you only find in strange “arty” types who dress in strange clothes, not something that is applied to problems occasionally in a superficial way… we wanted to get the idea across that creativity is a critical thinking skill that applies to all disciplines, in all sorts of ways, all of the time. Melinda and I both had backgrounds in the creative arts as well as science and engineering, so we found it easy to weave this into our planning. To make the point, at the social event held the evening before the conference officially started, we got up on stage to promote our cohort sessions, me dressed in Elmo pyjama pants and a set of large donkey ears, and Melinda in a giant chicken outfit. At least we got noticed!

So, in a 24 hour period, we went from having a cohort session with no structure, no content and no ideas, to having a session which was highly personalised, based on meeting the needs of the participants and built on the strengths of the facilitators. I might write more about the cohort sessions later, but I felt like it was a great success.

The other component of the conference was the unconference. Again, the problem with traditional conferences is that you sometimes don’t learn what you’d really like to learn, and it treats the “presenters” and the “audience” as two groups. If you believe that learners and teachers can have a much flatter relationship that that, the unconference model makes a lot of sense. At the first social event of the conference, participants were encouraged to write on a large sheet of paper a topic that they’d like to learn about. Equally, they were also encouraged to write down a topic they’d like to share about. These pieces of paper were then sticky-tacked to the wall and people could add a vote to the ones they were interested in the most. The ones that had enough votes then ran in the next unconference session time.

The other component of the conference was the unconference. Again, the problem with traditional conferences is that you sometimes don’t learn what you’d really like to learn, and it treats the “presenters” and the “audience” as two groups. If you believe that learners and teachers can have a much flatter relationship that that, the unconference model makes a lot of sense. At the first social event of the conference, participants were encouraged to write on a large sheet of paper a topic that they’d like to learn about. Equally, they were also encouraged to write down a topic they’d like to share about. These pieces of paper were then sticky-tacked to the wall and people could add a vote to the ones they were interested in the most. The ones that had enough votes then ran in the next unconference session time.

So, for example, I offered to run a session on teaching kids to think using Scratch, since I’ve been doing a lot of work on this back at school. So, I offered the topic, volunteered to be a presenter for it, people selected it, and it ran successfully. Conversely, someone else added a request for a session about Photoshop. They were not willing or able to run it themselves, but they were very interested in learning about it. Because I’m a bit of a Photoshop guy, I was happy to add my name to that as the presenter, and the session went ahead. This is really the spirit of an unconference. It’s about flexibly and dynamically connecting learners together to learn about the things that interest them. You can’t plan that sort of thing in advance because you have no advance idea of what those interests will be. An unconference only works if you place your trust in the wisdom of the crowds, if you believe that none of us is as good as “all of us”. If you believe that someone in the crowd will have the expertise to share with others, and the humility to accept that that expertise can come from anywhere, then learners become teachers and teachers become learners and our learning environment becomes flatter and less hierarchical. It goes from being about teacher and student, moving away from being about “us and them” to just being about “us”. And this is so much more reflective of the way true learning actually works.

This is really the spirit of an unconference. It’s about flexibly and dynamically connecting learners together to learn about the things that interest them. You can’t plan that sort of thing in advance because you have no advance idea of what those interests will be. An unconference only works if you place your trust in the wisdom of the crowds, if you believe that none of us is as good as “all of us”. If you believe that someone in the crowd will have the expertise to share with others, and the humility to accept that that expertise can come from anywhere, then learners become teachers and teachers become learners and our learning environment becomes flatter and less hierarchical. It goes from being about teacher and student, moving away from being about “us and them” to just being about “us”. And this is so much more reflective of the way true learning actually works.

Of course, you can see why this is risky. If participants turn up as empty vessels waiting to be filled, who see professional development as something that is done “to them” by someone else, then this is all destined to fail miserably. What I like about the unconference model is not just that it’s a far superior way to learn – because it is – but that it works on the underlying assumption that people are inherently good. It’s based on the fundamental ideals of sharing and teamwork, and the belief that most people are just as eager to give as to take.

It assumes the best from people, and that’s always a better environment to work in.

Firstly, mainland China is somewhere I’ve always wanted to go. In particular, Shanghai is fascinating because of its almost incomprehensible growth. Intellectually, I know that China is a fast rising star, rapidly moving from a developing nation to a developed nation. We’ve all heard the statistics about the size and growth of China, of how Chinese is destined to become the most used language on the Internet, of how China has more honours students than the US has students, and so on. Seriously though, no matter how many times I see the “

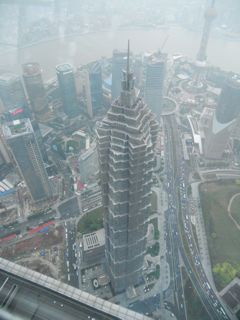

Firstly, mainland China is somewhere I’ve always wanted to go. In particular, Shanghai is fascinating because of its almost incomprehensible growth. Intellectually, I know that China is a fast rising star, rapidly moving from a developing nation to a developed nation. We’ve all heard the statistics about the size and growth of China, of how Chinese is destined to become the most used language on the Internet, of how China has more honours students than the US has students, and so on. Seriously though, no matter how many times I see the “ Then yesterday I was on the 100th floor observation deck of the

Then yesterday I was on the 100th floor observation deck of the  The third reason I’m so excited to be here in Shanghai is the people. My PLN came to life in a whole new way yesterday as I got to meet in person an amazing group of educators that I’ve only ever known online. I was sitting in a planning session yesterday, sharing the conversations with people like

The third reason I’m so excited to be here in Shanghai is the people. My PLN came to life in a whole new way yesterday as I got to meet in person an amazing group of educators that I’ve only ever known online. I was sitting in a planning session yesterday, sharing the conversations with people like