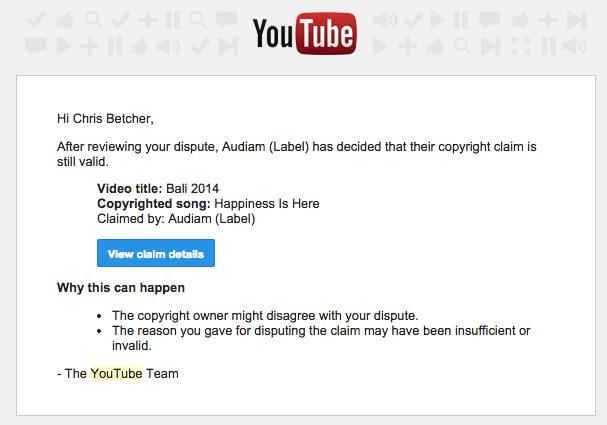

Here’s the follow-up from my last post about the copyright claim that YouTube made on a video I made using a Creative Commons soundtrack. You can read the previous post for the start of the story if you’re interested.

Since then, I’ve had conversations with several people about the issue. One was Jeff Price, the CEO of Audiam. Audiam was listed by YouTube as the entity responsible for policing the claim. Audiam is a service that musicians can use to track the use of their music in YouTube, although I think they also monitor Spotify and a few other streaming services as well. Basically, when a musician signs up to use Audiam’s services they upload a sample of their music which gets passed on to YouTube and fingerprinted. Fingerprinting is a process whereby the track can be compared against existing tracks to see if it matches, thereby identifying the copyright status of the music. If a match is made, YouTube flags it as a copyright violation and that was the problem I was having. It’s all done algorithmically of course, there are no actual people involved in the process, and in principle it’s a great idea.

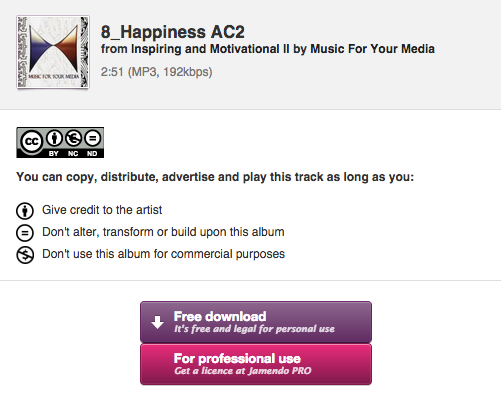

My contention was that the track in question was a Creative Commons licensed track and therefore had been incorrectly identified by the system, so I appealed the infringement claim by YouTube/Audiam.

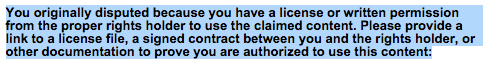

I had a few back and forth exchanges with Jeff Price about the problem. While we probably didn’t quite see eye to eye on everything, overall I thought it was a productive conversation. I was impressed and thankful that Jeff took the time to engage in the debate with me, although in the end, I didn’t feel that anything was really resolved. Basically, Jeff insisted that if I wanted to track to be released from the copyright claim I had to contact the musician and get them to ask Audiam to exempt my use of it. My argument was that a Creative Commons license was designed to avoid the need to do this and that it already grants that permission in advance. Jeff didn’t contradict me on this point, he just insisted that I either buy a license or get an exemption.

The most informative exchange I had was with the actual musician who created the piece, a guy called Enrique Molano. It took a bit of online detective work to find out who was responsible for the track but I eventually connected with Enrique through LinkedIn, where I discussed the issue with him. And that’s where it got interesting…

So here’s the lesson part of the story.

Enrique replied, very nicely, with a link to a support thread from Jamendo that contained the following information…

(No Derivatives is) the most misunderstood paragraph of the CC license. People think that as long as they don’t cut or trim the music, they can use it for their videos, but this is not true. Music with ND attribute is for listening only. You can make unlimited copies of it on various mediums, include it in playlists and compilations, embed it on websites, use it as music on hold or business background music, but you can’t use it as soundtrack for videos, games, audiobooks, presentations, etc. As the legal code says:

“(you can) make such modifications as are technically necessary

to exercise the rights in other media and formats, but otherwise

you have no rights to make Adaptations.”

People often argue that using an unaltered song as a soundtrack to a video does not make the video a derivative work, because the song itself is not recast or transformed in any way. That’s where “Don’t build upon this work” takes place. Coupling the music with additional content such as images, audio, or motion picture, is considered “building upon”. The legal code is very explicit about it:

“For the avoidance of doubt, where the Work is a musical work,

performance or phonogram, the synchronization of the Work in

timed-relation with a moving image (“synching”) will be considered

an Adaptation for the purpose of this License.”

Thus, as far as No Derivatives licenses are concerned, videos that use an ND-licensed song violate the terms of the license.

Say what?! I use Creative Commons a lot, and this is certainly not what I’ve been led to believe. I’m guessing that many of you may have also been under the same misconception. I’ve always understood that the No Derivs component of a Creative Commons license means that you can’t remix, change or edit the music, but I never realised that limitation extended to using the track, unchanged, as a soundtrack. But apparently this IS the case. Using a CC license with an ND property means you are NOT allowed to build upon the work, including using it as a soundtrack to a video.

The fact is, putting a CC BY-ND-NC license on a piece of work is just about as restrictive as leaving a full Copyright license on it. You still can’t really use it for anything without permission or paying.

While I feel a bit foolish not knowing about this detail of the ND license, I’m apparently not the only one. In his email to me, Enrique said “Sorry about the inconvenience. We’ve got about 200 claims from Audiam, apparently all of them under the same confusion.” I don’t like being wrong but I am glad that this little journey taught me some things that I didn’t know. Engaging in the conversation with Jeff Price was interesting and useful (although we could have avoided a lot of our back and forth had he simply pointed out that an ND track can’t be used as a soundtrack under the terms of the CC license). I’m thankful that Enrique eventually pointed it out, and that caused me to delve into a whole lot more background reading about Creative Commons, including re-reading the actual legal code in these licenses. I also learned there are significant wording changes between CC v3.0 and CC v4.0.

But at the end of it all, I learned the bottom line. If you want to use Creative Commons music with an intention of including it in a video, even if you don’t modify or remix the actual music track itself, DON’T use a license that includes the ND property.

If you produce content and your intention is to share it, and if you want to provide others with the necessary permissions to build upon your work, stick to one of the “Culturally Free” licenses, either CC BY, or CC BY-SA. Even a well intentioned use of No Derivs (or even Non Commercial) just causes a whole lot of headaches for those who want to legitimately build upon your work.

Featured image “I love to share” from Creative Commons HQ on Flickr