One of the things I feel quite strongly about is encouraging the responsible sharing of educational content through appropriate open licenses. There are lots of problems created by traditional copyright, and anyone who works in a school knows just how silly the copyright rules can be at times. While I understand the need for content creators to protect their work from being stolen and to protect their right to make a living, there are many times when the rules imposed by traditional copyright just seem completely absurd.

I’ve pushed the idea of Creative Commons for a number of years now, and I try to make sure that everything I produce is published under a CC license. I want to share by default, not by exception, and I can’t help but imagine what a better world we’d live in if everyone did the same. It’s so ironic that so many teachers are the most blatant abusers of copyright, yet feel so affronted when it’s suggested that they license their work in a way that might allow others to use it freely.

For quite a while now I’ve put a Creative Commons Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share Alike license (or CC BY-NC-SA) on this blog (and most of the other sites I publish). I originally decided on that license type because it seemed logical to me… it implied that you can use my work without the need to seek permission so long as it was attributed to me, you didn’t restrict others from also taking it from you, and you didn’t make money from it. It seemed logical.

Tonight, as part of the Open Education Content for Educators course I’m doing with the Wikimedia Educators group, I read an article called The Case for Free Use: Reasons Not to Use a Creative Commons -NC License. I’d heard other people talk about why, for educational purposes, it’s a good idea to not include the Non-Commercial limitation in a CC license, but I’d always included it anyway because, while I’m happy to share, there’s a part of me that doesn’t really want to see other people getting rich off my work. However, I’ve realised that including the -NC limitation raises a whole lot of other issues that I hadn’t considered, and may actually make it harder to use my work than traditional copyright. I don’t want that. I want to be able to share freely, and to allow anyone to make use of what I create and write.

The use of an -NC license is very rarely justifiable on economic or ideological grounds. It excludes many people, from free content communities to small scale commercial users, while the decision to give away your work for free already eliminates most large scale commercial uses. If you want to obtain additional protection against large scale exploitation, use a Share-Alike license. This applies doubly to governments and educational or scientific institutions: content which is of high cultural or educational value should be made available under conditions which will ensure its widespread use. Unfortunately, these institutions are often the most likely to choose -NC licenses…

…Recognizable and genuine free content communities can only evolve around the principle of true freedom. You have the chance to send a clear message whenever you license your own works. You have the chance to be heard, amplified by the voices of free content supporters around the planet.

For this reason, I’ve decided to remove the -NC requirement and change the Creative Commons licence on this blog to a CC BY-SA licence.

If you also publish work under a Creative Commons license, I’d encourage you to have a read of this article and consider opening up your content to help build a freer, more open world.

As an aside, one of the conversations we are having at my school at the moment is about changing our mindset about the content we create, and perhaps making everything we do available under an OER or Creative Commons license. For a large independent school like ours this is a big step, since in many ways, our content is a valuable commodity and is part of the reason that parents send their children to our school. Some would view it as our competitive advantage, and the notion that we might make it freely available is seen by some as crazy. But nonetheless, we are serious about investigating ways to license what we create as Open Educational Resources and to look at lifting that ridiculous rule that says everything you produce while at school is copyright owned by the school, not the teacher. We want to find ways where it can be used freely by both. I have no idea just where this discussion will end up, and just how open and free we might be able to make things, but for a school like ours it’s wonderful to seethat we are even having the conversation.

PS: If you have a WordPress blog, you might like to use the Creative Commons Configurator, a free WordPress plugin that adds both human and machine readable information to your posts. It’s super easy to use, and is one of my favourite WP plugins.

If you use Microsoft Word, there is also a free add-in you can install called the Creative Commons Add In for Microsoft Office. It adds a button to the ribbon that lets you include a CC license of your choice to any printable document. If you must use Office, it’s a nice add-in to have.

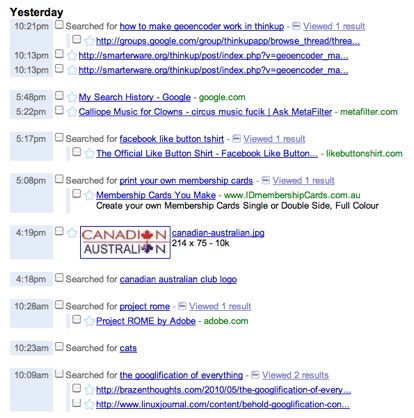

Many people don’t realise it, but if you use Google’s search services while signed into your Google account (which you already have if you use Gmail) then

Many people don’t realise it, but if you use Google’s search services while signed into your Google account (which you already have if you use Gmail) then  Whether we like it or not, in a digital age we all leave a trail behind us.

Whether we like it or not, in a digital age we all leave a trail behind us. I’ve been following a discussion online about school

I’ve been following a discussion online about school