Imagine this scenario… you are suddenly diagnosed with a life threatening disease, something very dangerous but quite curable if you have the right information about how to do so. Your doctor knows that there is an answer to your serious problem, but cannot recall what drug is required to treat it. He remembers reading something about it a long time ago, but can no longer recall the exact name of the drug.

Imagine this scenario… you are suddenly diagnosed with a life threatening disease, something very dangerous but quite curable if you have the right information about how to do so. Your doctor knows that there is an answer to your serious problem, but cannot recall what drug is required to treat it. He remembers reading something about it a long time ago, but can no longer recall the exact name of the drug.

He reaches towards the mouse on his computer, and begins to click a link that will take him to the online medical directory where he will find the answer he needs to cure your condition.

“Stop!”, you declare. “That’s cheating! If you can’t remember the name of that drug without looking it up, then what sort of doctor are you? I want you to just remember it without looking it up.”

Of course, I imagine that if this situation were real you would be only too happy for the doctor to do whatever was required to find the cure for your disease. You wouldn’t think twice about whether it might be considered “cheating” to look up the information needed to save your life… in fact you’d better hope that you have a doctor who a) knows there is an answer out there somewhere, and b) knows how to find it quickly.

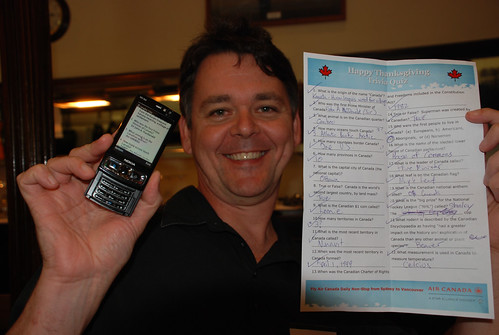

I pondered this scenario today because I went to a dinner party with about 40 other people and we were presented with a trivia quiz on the table, something to keep us busy and entertained between food courses. Being a celebration of Canadian Thanksgiving, the questions were all about Canada. Now, I actually know quite a bit about Canada… I lived there for a year, travelled quite extensively through the historic eastern provinces, read a few books about Canadian history, and I have a Canadian girlfriend. So I did know the answer to quite a few of the questions.

Of course, there were also questions I didn’t know the answer to. And being the curious type who likes a challenge and to always learn more, I reached for my Nokia N95, pointed it to Google, and started looking for the answers to the questions I didn’t know. If you have reasonable information literacy skills and can come up with good search keywords, finding answers to simple recall-style questions with Google is pretty easy. In fact, you can usually find the answers just from the Google search results page without even going to the websites they link to. It was not long before I had the elusive answers… in fact, I actually stumbled across the exact quiz that the questions were lifted from. Whoever put the quiz together had not changed anything, just used it directly from this website. I casually copied down all the unknown answers onto the sheet and waited until it needed to be submitted.

Of course, when the sheets were finally collected and tallied, there was general astonishment that someone could have actually gotten all the questions 100% correct! A few people who knew what I’d done bandied about words like “cheating” and “unfair”.

For the record, I did not accept the prize – a lovely bottle of red wine – because I willingly admitted I had some help from my friends Mr Google and Mr Wikipedia, and I figured it would not have been fair to accept the prize. I guess I just like to be a bit of a stirrer sometimes in order to make a point, even if only to myself.

But seriously, why do we build entire education systems based on rewarding people who can respond with the correct answers to questions, but then assume that any use of a tool to help them do this is cheating? Why would a doctor in the scenario above get applauded for doing whatever was necessary to find an answer to the problem, but a student who does the same thing is considered a cheat.

If basic recall of facts is all that matters, a tool like Google can make you the smartest person in the room. Today’s trivia quiz proved that. If finding answers anywhere at anytime is a valuable thing to be able to do, then a mobile phone should be a standard tool you carry everywhere.

What I think people were really saying was that, if I was allowed to use my phone to find answers and everyone else wasn’t, then that would give me an unfair advantage. And that may be true if I was the only person with access to Google, but the fact is that I didn’t do anything that every other person in that room could have done if they’d have chosen to. The fact is, I was the only one in the room who used a tool that we all potentially had access to, but because I used that tool it made me a “cheat”.

And here’s the real point… mostly we ban these tools in our classrooms. And we generally consider any student that uses such tools to find answers to our narrow questions to be a cheat. And we drill into kids that when we ask them questions, when we set up those “exam conditions”, they better not even think about being “enterprising” or “creative” or “problem solvers”… Just know the answers to the questions, and show all your working too, dammit.

And you’d better hope that if one of those students ever grows up to be your doctor, the rigid thinking we may have instilled in them about “knowing the answers” has been replaced with a far more flexible skill for “finding the answers”. Let’s hope that our kids don’t have too much trouble unlearning all the bizarre thinking that schools spend so much time drilling into them.

What do you think? At what point does the ability to find answers cross the line and become cheating?

![]() Where does cheating begin? by Chris Betcher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Where does cheating begin? by Chris Betcher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The real issue about cheating has always been passing others’ work off as one’s own. In extreme cases, as at universities, it is the most fundamental of all theft: your identity and accomplishments are stolen. Imagine going to a job interview and rattling off your PhD thesis and publications only to be told by the interviewer “We’re familiar with that but we know that it was written by so & so”. This is not far-fetched. It happened to a colleague. Her career was ruined. The thief got a promotion. As we move toward ‘open source’ one thing is sure – the fat cats always make sure their name is on everything as author – whether they wrote it or not. Research assistant drones will only fall further behind. … and we wonder why we can’t get kids interested in science careers!

Check out this article from the Sydney morning post relating the trial of using cell phones in exams.

Phone a Friend Exam’s

http://www.smh.com.au/news/athome/phone-a-friend-in-exams/2008/08/20/1218911794460.html

@Dan Robinson… Funny you should mention that.

http://betch.edublogs.org/2008/08/20/the-truth-is-out-there/

I work at that school.

Thanks to everyone who contributed to this thread. It’s been wonderful to watch the discussion unfold over the last few weeks.

Just for the record, I totally agree that there must be baseline standards in “knowledge” and I’m not suggesting that we dump the idea of learning and recall in favour of being ignorant but armed with a cellphone.

I often think about it like this… when you’re putting a jigsaw puzzle together, the first few pieces are really hard because you have no reference points. You have all those blue pieces that you know are part of the sky, but it’s hard to join them together at first. As you gradually get more pieces on the table it gets progressively easier to figure out where the next piece goes. The last few pieces are really easy because there is so much of the rest of the puzzle in place… the more pieces you get the more you, quite literally, get the big picture.

Learning facts and remembering information seems kind of similar. If you don’t have a good general knowledge, then it’s hard to connect the pieces as you “learn” new facts. You get presented with them, but if you don’t have a lot of other “knowledge” to hang those new facts on, they often just don’t connect in your schema of the world. If you have a pretty good general knowledge you are probably more likely to learn new facts more effectively because many of them will be building on things you already know. The more you know, the more you know.

Just having access to something like Google won’t help much if you have a limited ability to connect the facts you discover. Well, it will, in that you can “find answers”, but you probably won’t build real learning.

And that’s where I think a teacher brings value to the learning process. Although we all espouse the value of a student-centered learning process, it’s a wise teacher, providing explicit teaching that’s the link between just helping kids to know stuff, and helping kids to learn how to learn, helping them to know how to find information when it’s needed, helping them to connect the dots.

All of you who spoke about the idea of “just Googling” not being enough, you’re absolutely right. But it’s a useful skill to be able to find information on demand when you really need it. It just needs to be seen as one of the skills – literacies – of living in today’s world, as is just another way that we keep adding pieces to the jigsaw puzzle.

Hi Chris,

I have seen my family doctor on many an occasion pull out his CPS (Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties) to look something up, err, cheat, help my kids get better. I was glad he did.

Simon

Yes the ability to use tools to find information is a skill students need to learn. But so is the ability to learn how to study so that they can recall information. No I don’t care that a student remembers the symbol for Manganese in 30 years – but the skills that I should have taught him in order to remember that information at least for a little while are important.

I agree that this is a sticky situation. We all want our students to study and know the material so that they can answer the questions on the test. As a student I was always saying, “this is dumb. I will never need to know this in the ‘real world’ and if I do I can just look it up!” I think some things really don’t need to be memorized. For me, an elementary school teacher, I will not need to know how to find the derivative of an equation and if for some unknown reason I really do, I can just look up how to do it. Some things, however, I do need to know so I can teach my students. I need to know grammar and basic math. I guess the challenge becomes determining what type of information really needs to be learned, and what information we can just look up using our resources.