After a successful iPad trial at school last year, the teachers all agreed it was working really well. So this year we asked our year 5 and 6 students to bring an iPad to school and I’ve been working with the teachers and students in those classes to help ensure we get the most from this arrangement. I think it’s been working really well; the kids have been incredibly responsible and have been producing some really interesting work with them.

I had an email from a Year 5 parent a few weeks ago asking some questions about the iPad program, in particular about required apps, the rules and expectations for their use, the use of games (including one called Goldrush that she was concerned about), impacts on socialisation, responsibilities for backing up data, etc. In particular, this parent had a few concerns about using the iPad for playing games versus using it a a learning tool. I wrote a fairly long and detailed email in reply, and I’m republishing it here (anonymised of course) because I thought the general gist of my reply might be of some value to others. Your thoughts are welcomed in the comments.

The guts of the email went like this…

One of the key aspects of the students using iPads as BYO devices is that it provides (by design) an environment and opportunities for them to become managers of their own technological world. It also means that parents have a significant say in what they want to allow or not allow on their child’s iPads. Most of what we covered at the parent information night back in Term 1, prior to the students being allowed to bring in their iPads, was focused on reinforcing this idea that in a BYOD environment the final say on what is appropriate is up to individual parents. As I tell the kids all the time, “I don’t live in your house, so I don’t make the rules for what you do there. Your parents do”.

We initially asked the students to have only a fairly small set of designated core productivity apps installed on their iPads – a web browser, word processor, presentation tool, PDF/eBook reader, video and audio editing tools, etc. We have intentionally not made long lists of “required apps” because the nature of operating a BYOD program is such that students should be allowed to choose the tools (in the form of apps) that work best for them. For example, in a recent task, students had an option to produce a set of presentation slides (what in a non-iPad world you’d just refer to as a “PowerPoint”) The task was structured in such a way that students could respond to this task using a variety of presentation-style apps, including Keynote, MoveNote, PopBoardz, Haiku Deck, SlideIdea, Flowboard, and others. Part of the learning we want to occur is that students are given opportunities to make good decisions about which technology tools they wish to use, and allow them to identify, find and manage those apps. In finding new apps they also develop the very important skill of learning how to use a piece of software that they have never seen before. What this amounts to is a way of helping students “learn how to learn”, which is possibly the most important skill they can take away from the whole experience of school.

Regarding games, it’s sometimes not easy to know what exactly constitutes a “game”. For example, Scratch, Minecraft, even Mathletics, could all be considered to be “game-like” but are incredibly valuable learning environments that we actively promote and support. For example, a game like The Room requires a high level of problem solving and lateral thinking skills. Games like Threes! or 2048 involves the use of logic, problem solving and maths. Musyc is a music composition tool that looks very much like a game. There is an app called DragonBox in which the rules are based on the principles of algebra, essentially teaching students to understand algebra through playing the game. I haven’t played Goldrush myself, but I just had a quick look at it in the App Store and it looks like it has quite a few valuable learning aspects to it, including engineering concepts and bridge construction skills (something the students will do much more of in Year 6 next year) and it looks like it needs a lot of thinking, problem solving and logic to play well.

While it’s probably true that some games don’t offer enough learning for the amount of time put into them, I would be vary wary of having a simplistic “games = bad” approach, or to think that games (or game-like environments) cannot help students learn valuable skills. Much of the research around gaming suggests quite the opposite, and that the engagement factor present in most games, as well as the logic and problem solving skills usually required, are in fact exactly the kinds of things we need to be developing in our students.

To be clear, I am NOT saying that students should spend all their time playing games. However, the evidence suggests that there is much to be gained by allowing students to spend SOME time with games, particularly games that support worthwhile learning objectives.

I think we could have a whole other discussion about what exactly we mean by the term “game”, what a “game” looks like, and what might constitute using the iPad as “a learning tool”. I suspect the distinction may not be as clear cut as it might first appear. And because every family will have different perspectives on this distinction, this needs to be a conversation that takes place between parents and their child. If you’re unsure about an app, be it a game or anything else, by all means sit down with your child and talk with them about it, ask what they likes about it, what they learns from it, and get them to show you how they use it. As I pointed out at the parent evening, the ultimate decision about iPad use, about what apps are appropriate, about where and how the iPad gets used at home, rests with parents. I repeatedly said to all parents “It’s your house, your child, your iPad, your rules”.

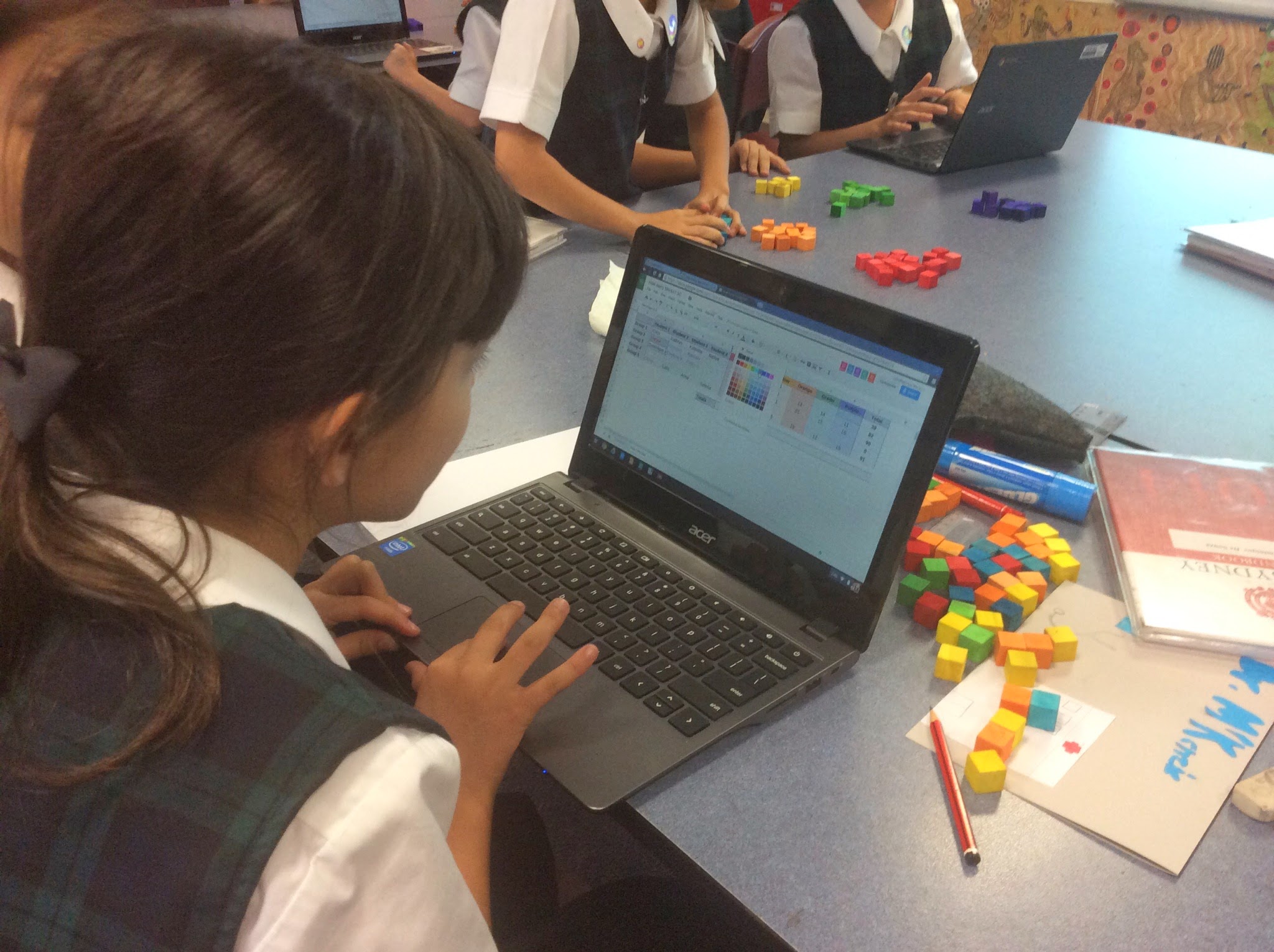

As far as use at school goes, the iPads have been very successful so far in extending learning opportunities. Certainly, in the work I’ve been doing with the students they have shown some amazing learning with these tools. A large part of that has come about because we have not mandated specific apps or uses of the devices, and instead are allowing each student to use the devices in ways that best support their own learning, using apps that work best for them. I recently had one of the iPad classes do an “App Slam” where they each had 2 minutes to stand up in front of the class and present an app, a tool, a website, etc, that they found useful or fun. It was amazing to see not only the confidence and fluency with which they used this technology, but also the ease with which they shared it with the class. And interestingly, out of the 16+ apps on show, I’d only heard of two of them before. The point is that with the hundreds of thousands of apps in the Apps Store, the students are taking the lead here and discovering useful tools that we teachers may not.

Some of the innovation, independence and creativity we have seen so far has been astounding, and has taken the learning into places that simply could not be achieved without these tools. The goal with using technology in education is not simply to use technology to reproduce things we COULD already do without it, but to find entirely new ways to do things that we COULD NOT do with out it. So while using the iPads to take notes, read books and look things up online are all worthwhile and valid uses, the really powerful learning will come from getting the students to interact with data, ideas and skills that could not be previously done without them. And even after just a term and a half of having the devices we are starting to see many instances of this happening.

The teachers of year 5 and 6 are very aware of the students using their iPads in appropriate and socially responsible ways. Their use is managed in class and any student who gets off-task is very quickly brought back to the task at hand. I am told that the students do get some free time with the iPads, but only on Thursdays, only at lunchtimes and only in the library, so that seems like a fair deal to me.

Regarding data monitoring, when the students are at school they are connected to our school wifi so they are subject to all the usual filters and blocks that apply to Internet access on our network. However, we don’t (and really don’t want to) restrict students from downloading new apps, for all of the reasons I’ve outlined above.

Regarding backup, we use Google Apps for Education as our core platform here school so any documents that the students store in that service are securely backed up in the Google cloud. If they put their work into Google Drive (as most of them do) it will be safe. Other file types (such as photographs, iWork files, etc, may be managed by Apple’s iCloud service if the student enables it. Aside from that we do recommend that all students back up their iPads to iTunes on a home computer regularly. Because it is a BYO device, the responsibility for doing this lies with the student (and their parents if needed) Again, our students are growing up in a world where the process of managing data is increasingly important and will usually not be done for them. It’s important they start learning to do this now.

I’m not a big fan of Christopher Pyne. As far as I’m concerned, our new federal education minister has shown himself to be inept and completely out of his depth in his current portfolio. He continually implies that Australia’s teachers are less competent than they should be and that our students are not receiving a proper education.

I’m not a big fan of Christopher Pyne. As far as I’m concerned, our new federal education minister has shown himself to be inept and completely out of his depth in his current portfolio. He continually implies that Australia’s teachers are less competent than they should be and that our students are not receiving a proper education.